The Monster Among Us: Frankenstein from Mary Shelley to Mel Brooks

Date:

27 April 2008 – 16 November 2008

Location: Dome Room, UVA Rotunda

Curated by: Shannon Gorman '08

This exhibition traces the evolution of the myth of the Monster from Shelley’s 1818 publication through to Mel Brooks’ “Young Frankenstein”. The story is one of the commodification of horror, the infiltration into our societal consciousness of issues associated with technology, and the ways we as a society have taken the nightmare of a young women and grown it into our first modern myth.

We present about 145 books, dolls, posters, masks, and other items that tell the story of the Creature’s changing relationship to modern culture. Almost all of the materials shown are from the collection of Susan Tyler Hitchcock, author of a recent book, Frankenstein: A Cultural History (New York: W. W. Norton & Company). Where will our sympathies ultimately end up; with the monster, or the creator?

Title-page of the first edition of Frankenstein

Mary Godwin (she would become Mary Shelley) was 19 years old when she wrote Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus. In 1816, she and her lover, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, spent the summer on the shores of Lake Geneva, in Switzerland. Lord Byron was a neighbor, and the group around him amused itself during rainy weather by reading—and writing—ghost stories. Frankenstein was Mary Shelley’s response to the contest. The novel was published anonymously in London in 1818 (Shelley’s name did not appear on the title-page of the book until a later edition).

Though the novel received generally unfavorable reviews, it was an immediate popular success. Theatrical versions soon appeared, and it was translated into French. The author published a revised version of the novel in 1831, with a new preface explaining the circumstances of its composition. Well before the end of the 19th century, “Frankenstein” was a common synonym for “monster”—even though, properly speaking, Frankenstein is the name of the man who created the monster, not the name of the monster itself: Mary Shelley never gave her monster a name, variously calling him creature, daemon, devil, fiend, monster, ogre, and wretch.

Boris Karloff as Frankenstein on a 1997 US postage stamp.

The first silent film based on the novel appeared in 1910 (a graphic novel adaptation of that film appears in this exhibition, as well as a copy of a re-mastered DVD version). The 1931 Universal Studios version of “Frankenstein”, directed by James Whale and starring Boris Karloff, accelerated the process of turning the creator and his monster into a ubiquitous myth. James Whale’s treatment significantly altered the original story (for example, in the novel the monster is created through chemical, rather than electrical, means).

Playbill for “Young Frankenstein”.

A great many films based on the Frankenstein characters have appeared since 1931, notably “Bride of Frankenstein”, again starring Karloff and directed by Whale (1935); “The Ghost of Frankenstein”, with Lon Chaney, Jr. (1942); “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein”, a parody version (1948); “The Curse of Frankenstein”, with Christopher Lee as the Monster (1957); “I Was a Teenage Frankenstein”, a sequel to “I Was a Teenage Werewolf” (1957); “Frankenstein Meets the Spacemonster”, with marauding Martians looking for Earth women (1965); “Dracula vs. Frankenstein”, said to be one of the worst movies ever made (1971); “Young Frankenstein”, starring Gene Wilder and directed by Mel Brooks (1974); and “Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein”, directed by Kenneth Branagh (1994). “Young Frankenstein”, Mel Brooks’ musical comedy version of his 1974 movie, opened on Broadway in November of last year.

“The greatest horror story of them all,” according to the cover of this 1953 mass-market paperback edition of “Frankenstein.”

The circle in which Mary Shelley moved was fascinated with such phenomenon as galvanism, by which a corpse could be made to spasm as though alive through the application of electrical current. Her own father, William Godwin, hoped for medical improvements that would prolong life. But with the excitement of scientific progress also came the fear that men would push the boundaries too far. While many Frankenstein movies have trivialized or satirized that fear, a serious worry threads its way though the modern Frankenstein tradition: what happens if we get too close to the edge of creation?

The Monster Among Us: Frankenstein from Mary Shelley to Mel Brooks attempts to show how a young woman’s tale has grown into a societal myth. The items on view document a movement towards the commodification of horror, moving from Edison’s 1910 film version, which took great pains to not scare or offend anyone, to more recent versions which (when they are not simply goofy), count on our willingness to pay to be scared. The closer we get to being able to create artificial life forms, the more immediate Dr Frankenstein becomes in our imaginations.

Changing societal values have altered the way that we interact with the monster myth. We have begun to allow the Monster into our children’s spaces; he is not always considered dangerous. As technology changes, the things that scare us change; and so our myth-making alters to fit our needs.

At the end of the day, Frankenstein will always be a story of dueling tensions: we wish to seek knowledge, but we must not push the boundaries of knowledge too far.

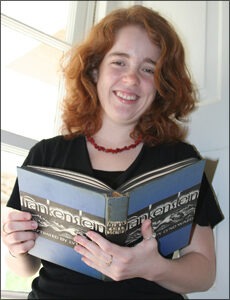

Exhibit Curator Shannon Gorman, UVA 4th-year

Front of the dust jacket of Hitchcock’s Frankenstein: A Cultural History

Most of the items on view in this exhibition were lent by Susan Tyler Hitchcock, whose interest in the Frankenstein myth culminated in the recent publication of Frankenstein: A Cultural History (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2007; see illustration to right). I am grateful to her for her mentorship, as well as her generosity in lending this material. I am also indebted to Terry Belanger, Barbara Heritage, Kenneth Giese, Ryan Roth, Dan Bryant, Paul Pugliese, Laura Barba, Kelly Webster, and Stephen Greenberg for their very different, but very important contributions, to this show.