The Lives of the Autograph Collectors

Date:

17 January 2003 – 1 May 2003

Location: Dome Room, UVA Rotunda

Curated by: Nathaniel Adams '03

Washington Irving called autograph collectors “the musquitoes of literature.”

Washington Irving called autograph collectors “the musquitoes of literature.”

Nobody knows when people started collecting autographs. Historians of autograph collecting often point to sixteenth-century German students as the precursors to contemporary autograph hounds. Traveling scholars maintained books filled with letters of correspondence written by people they encountered during their Wanderjahren. Such an album served as a filing system for letters of introduction to future destinations along a student’s route. The impetus for these students to collect was therefore utilitarian; the value of the assembled signatures was in their ability to open doors, not intrinsic in the handwriting of the individual signers.

By the later eighteenth century, persons of leisure throughout Europe were assembling collections of correspondence and literary manuscripts written by the great men of politics and letters. The focus at that time was on monumental figures from the past; John Milton was an appropriately famous literary subject, and any number of continental royals would have been suitable targets. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, however, manuscripts and letters of living authors and statesmen had become the targets of ambitious collectors, as well.

Autograph collectors had two justifications for their activities: either for historical purposes (to preserve the original manuscripts of an important writer or politician), or to showcase the collector’s social status—while there did not exist a large economic market for autograph letters and manuscripts, to have access to them meant that you were a respected figure in the social circles where their authors resided (and where their written items circulated).

Autograph collecting in America did not begin in earnest until about 1815. Written accounts from nineteenth-century newspapers hail William Sprague of Albany and Israel Tefft of Savannah as the first major American collectors, although they were soon followed by a great many others. These early American collectors were in a curious position relative to their European counterparts. Whereas Englishmen could collect English authors, there had not yet developed a distinctive American literature, leaving Stateside collectors to seek out the writings of respected national and local statesmen (both historical and contemporary), as well as European writers. It wasn’t until the rise of national literary figures such as James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, and their contemporaries that autograph collecting in America shifted into high gear.

Autograph collecting in America did not begin in earnest until about 1815. Written accounts from nineteenth-century newspapers hail William Sprague of Albany and Israel Tefft of Savannah as the first major American collectors, although they were soon followed by a great many others. These early American collectors were in a curious position relative to their European counterparts. Whereas Englishmen could collect English authors, there had not yet developed a distinctive American literature, leaving Stateside collectors to seek out the writings of respected national and local statesmen (both historical and contemporary), as well as European writers. It wasn’t until the rise of national literary figures such as James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, and their contemporaries that autograph collecting in America shifted into high gear.

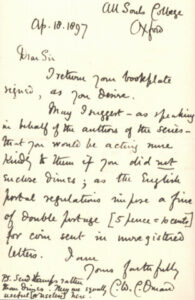

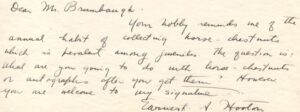

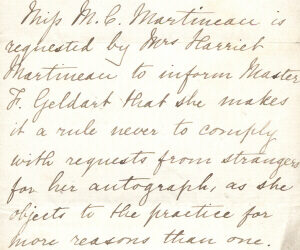

One historical indicator of the activity’s intensity may be the extent to which targets identified collectors as a nuisance. The visual motif of this show, a portrayal of autograph collectors as flying pests, refers to Irving’s caustic description of collectors as the “musquitoes of literature.” In reference to contemporary autograph hunters, Fitz-Greene Halleck (“the American Byron”) noted that “distinction has its penalties as well as pleasures”; and in an 1850 letter to Mrs. Hamilton Fish, Cooper stated that he would have no trouble sending her a dozen autographs, as he received (and apparently complied with) such requests from perfect strangers “almost daily.”

Increased demand fueled the development of a commercial marketplace for autographs. As the first generation of major American collectors began to disappear, their collections made their way to the public via auctions, which were first held in England in the 1830s, and later in the United States. Recreational clubs devoted to autograph collecting appeared in the middle of the c19, and by 1890 there had already been established at least one popular periodical devoted to collecting autographs: The Collector doubled as a forum for essays on collecting and as a price guide for prospective buyers. It was soon followed by full-length books on the subject.

The most notable trend of autograph collecting in the twentieth century reflected changing cultural values. Through the 1920s, the primary targets of autograph seekers were still literary, political, and high-ranking religious figures. However, the increasingly ubiquitous phenomena of motion pictures, radio, and television resulted in a tremendous shift in popular culture that placed most autograph hounds squarely within the cult of the media-accessible celebrity. Their targets might no longer be notably literate, but fans avidly hunted them down for their signatures, nonetheless.

Perhaps this is the aspect of modern autograph hounds that most confounds and intrigues us: that they seek to collect an aspect of celebrity that has virtually no relation to the talent or skills that created that celebrity in the first place.

The first known use of the term autograph hound occurs in a 1933 pulp magazine, Black Mask, where it denotes a collector with an especially voluminous portfolio. It appears to have replaced the nineteenth-century autograph hunter, a derogatory term for either those who were particularly aggressive in their approach, or those who resorted to misdirectional ruses to obtain a signature. (For example, an 1834 magazine published the results of one clever individual’s attempt to obtain the autographs of various authors by asking them to refer a prospective valet. The project was an unmitigated success.)

The first known use of the term autograph hound occurs in a 1933 pulp magazine, Black Mask, where it denotes a collector with an especially voluminous portfolio. It appears to have replaced the nineteenth-century autograph hunter, a derogatory term for either those who were particularly aggressive in their approach, or those who resorted to misdirectional ruses to obtain a signature. (For example, an 1834 magazine published the results of one clever individual’s attempt to obtain the autographs of various authors by asking them to refer a prospective valet. The project was an unmitigated success.)

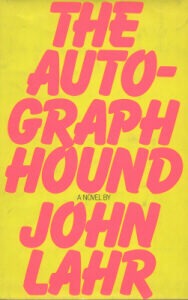

The canine comparison immediately found a place in the American lexicon. In 1939, Walt Disney produced a cartoon short called “The Autograph Hound,” in which Donald Duck sneaks onto a Hollywood studio lot in search of his favorite celebrities. (This should not be confused with Goofy’s 1956 comic-book adventure, “The Autograph Hunter.”) The year 1944 saw the first credited film appearance of a character named “Autograph Hound”: Betty Brewer in Cover Girl (though note that a 1936 “Our Gang” short credited May Wallace as “Autograph Seeker”). The autograph hound finally returned to his literary roots in 1973 with the publication of John Lahr’s novel The Autograph Hound.

Not surprisingly, the internet has had the largest impact on the nature of autograph collecting in recent years. Specialized chat rooms and message boards allow geographically distant hounds to share collecting tips. Net-based fan clubs offer collectors all the information they need to get the signature of a favorite star.

Not surprisingly, the internet has had the largest impact on the nature of autograph collecting in recent years. Specialized chat rooms and message boards allow geographically distant hounds to share collecting tips. Net-based fan clubs offer collectors all the information they need to get the signature of a favorite star.

For a small fee, online address books offer subscribers access to thousands of celebrity mailing addresses (some of which actually work!). Meanwhile, hardcopy autograph magazines have all but disappeared — the last in wide circulation are Autograph Collector and Autograph Times. Book-length guides to collecting continue to hit bookstore shelves, but they generally serve as reference works for authenticity verification and prices, rather than as historical primers. In any event, eBay seems rapidly to be rendering auction houses and retail stores obsolete for all but the most expensive autograph items—speaking of which, we extend our kind thanks to the Boston-based manuscript dealer Kenneth W. Rendell, whose generous donations to the Rare Book School collections over the years have made this exhibition possible.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of autograph collecting as a hobby has been its longevity. For more than two centuries, enthusiasts have taken undiminished delight in obtaining the scrawls of arbitrarily-selected individuals. It can serve as a source of comfort that our post-literate society still contains people with a healthy appreciation for the written word—or two.

The curator of this exhibition is Nathaniel Adams, a 4th-year undergraduate history major at UVA. He is currently researching an honors thesis on nineteenth-century collectors of Thomas Jefferson’s autograph letters. He signs his name below, for the benefit of autograph hounds new and old: