Reading with and without Dick and Jane: The Politics of Literacy in 20th-Century America

Date:

9 June 2003 – 1 November 2003

Location: Dome Room, UVA Rotunda

Curated by: Elizabeth Tandy Shermer '03

American educators, politicians, and parents have been fighting for a long time over the best way to teach children how to read.

William McGuffey’s phonics-based primers, which emphasized the sounding out of words by learning letter-sound associations, dominated American primary education from the middle of the nineteenth until the early twentieth century. During the Progressive Era, some educators and social scientists began to believe that McGuffey’s moralizing texts were too complex for young readers, and they argued for a simpler approach, one that used a carefully limited vocabulary and story lines that were more relevant to the lives of contemporary children.

After World War I, publishers began to produce primers incorporating some of the  changes John Dewey, William S Gray, and other experts advocated. In particular, illustrator Zerna Sharp worked with the Scott, Foresman publishing company and with William Gray to devise a series of basic primers that would include his suggestions. The new primers introduced characters with whom children could identify, and they contained stories featuring the same set of siblings engaged in normal day-to-day activities. To develop a national audience for the new series, the primers de-emphasized regional characteristics: there were no treks through snowstorms or into barren deserts.

changes John Dewey, William S Gray, and other experts advocated. In particular, illustrator Zerna Sharp worked with the Scott, Foresman publishing company and with William Gray to devise a series of basic primers that would include his suggestions. The new primers introduced characters with whom children could identify, and they contained stories featuring the same set of siblings engaged in normal day-to-day activities. To develop a national audience for the new series, the primers de-emphasized regional characteristics: there were no treks through snowstorms or into barren deserts.

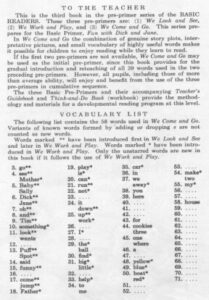

The result was Dick and Jane, who made their debut in 1930 in Scott-Foresman’s Elson-Gray Basic Readers, accompanied by a guide urging teachers using them in their classrooms to adopt the whole word (or look-say) method, one that emphasized the meaning of words, rather than using rote phonics drills. The primers constantly repeated the few words in their texts as a replacement for phonics exercises. To help teachers, each primer had a vocabulary list at the back of the book, with a paragraph explaining the number and relevance of the vocabulary words introduced.

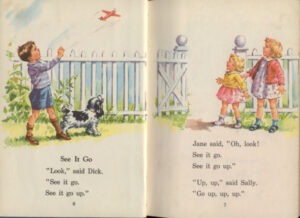

The Scott, Foresman series was heavily illustrated with pictures intended to help new readers associate a word with its meaning: a picture of Jane and Sally looking up at Dick’s flying airplane above a few lines of text repeating the word up, for example.

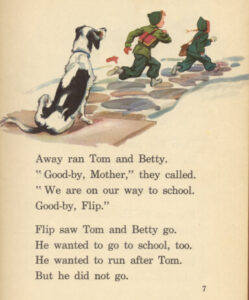

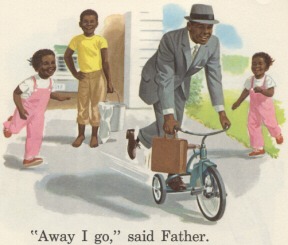

Scott, Foresman and Company retired the Elson-Gray series in 1940 but kept both Dick and Jane and the look-say method in its successors. The company had so much success with its Basic Readers that other publishing houses copied its formula (see illustration, from a primer published by Ginn and Co). All of these primers focused on simple stories about siblings living in Suburbia, USA. Each primer introduced only a few words at a time to readers and used pictures and repetition to make sure children learned the meaning of each word. But Dick and Jane dominated this market for a generation: the great majority of Americans learned how to read from Scott, Foresman primers and story books in the post-World War II era.

In the later 1950s and early 1960s, Dick and Jane found themselves in troubled waters. In 1955, Rudolf Flesch struck out against look-say readers in his bestseller, Why Johnny Can’t Read. Flesch argued that the whole word method did not properly teach children how to read or to appreciate literature, because of its limited vocabulary and overly simplistic stories. Other phonics advocates in the 1960s echoed Flesch’s arguments, calling for new primers that focused on phonics and introduced students to real literature.

1955, Rudolf Flesch struck out against look-say readers in his bestseller, Why Johnny Can’t Read. Flesch argued that the whole word method did not properly teach children how to read or to appreciate literature, because of its limited vocabulary and overly simplistic stories. Other phonics advocates in the 1960s echoed Flesch’s arguments, calling for new primers that focused on phonics and introduced students to real literature.

An act of Congress helped phonics advocates end Dick and Jane’s tenure in American school systems. In the mid-1960s, President Lyndon B. Johnson called for better primary education especially for underprivileged students. The resulting Elementary and Secondary Education Act included money to help poor school districts buy supplemental materials for their students but with the restriction that these materials had to have subject matter appropriate for urban schoolchildren. Scott, Foresman’s solution was to introduce a minority family into Dick and Jane’s formerly all-white world: Mike, his sisters the twins Pam and Penny, and their parents.

Meanwhile, phonics proponents continued to lobby for a return to McGuffey’s method. Scott, Foresman retired Dick and Jane in 1965. Two years later, the firm introduced its Open Highways series. These primers included poems and classic children’s stories such as the Gingerbread Boy. Like their predecessors, they used colorful pictures. But they were broadly multicultural, and they abandoned the use of repetition and word charts.

Scott, Foresman retired Dick and Jane in 1965. Two years later, the firm introduced its Open Highways series. These primers included poems and classic children’s stories such as the Gingerbread Boy. Like their predecessors, they used colorful pictures. But they were broadly multicultural, and they abandoned the use of repetition and word charts.

By the late 1960s, Dick and Jane were gone – but they were by no means forgotten: critics continued to attack them. When phonics proponents squared off against whole word advocates, they used excerpts and pictures from Dick and Jane readers as bad examples. Multiculturalists pointed out the lack of minorities and the racial insensitivities of the Scott, Foresman series. Feminists spoke out against sex stereotypes in the Basic Readers. Retrospectively, Dick and Jane began to symbolize for many the inadequacies of the entire Cold War era.

By the late 1960s, Dick and Jane were gone – but they were by no means forgotten: critics continued to attack them. When phonics proponents squared off against whole word advocates, they used excerpts and pictures from Dick and Jane readers as bad examples. Multiculturalists pointed out the lack of minorities and the racial insensitivities of the Scott, Foresman series. Feminists spoke out against sex stereotypes in the Basic Readers. Retrospectively, Dick and Jane began to symbolize for many the inadequacies of the entire Cold War era.

Nevertheless, Dick and Jane are still with us, and they remain (with their sister Sally, their dog Spot, and their cat Puff) virtually the only characters in the history of American primary education whose names have become household words. Many Americans remember the duo fondly, and they collect copies of the books in which they appeared.

I wish to thank Elena Siddall, a Dick and Jane enthusiast and curator of the Richmond Public Library’s celebrated 1997 Dick and Jane exhibit, for lending materials from her collection for the present exhibition. The collectors who shared their thoughts and memories of Dick and Jane with me were also invaluable resources who convinced me that I am probably the worse for not having learned how to read with Dick and Jane.