Comics in Circuit Interview: Haniyeh Barahouie

In order to showcase some of the many individuals who are creating, publishing, interpreting, collecting, and studying comic books and graphic novels today, the Rare Book School exhibition Comics in Circuit includes a series of monthly interviews by RBS Associate Curator Ruth-Ellen St. Onge.

The first interview is with Haniyeh Barahouie, a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in the University of Virginia’s Department of French. Her research interests include graphic novels, writing and gender, literary theory and aesthetics, digital humanities, literature and war.

When and how did you first encounter and begin reading comic books and graphic novels?

As a kid, I was always interested in visual stories. The first graphic novel that I encountered was The Adventures of Tintin by Hergé when I was 11 years old. I fell in love with Tintin’s character and his dog.

As a kid, I was always interested in visual stories. The first graphic novel that I encountered was The Adventures of Tintin by Hergé when I was 11 years old. I fell in love with Tintin’s character and his dog.

Why did you decide to focus your doctoral research on graphic novels?

When I first started thinking critically about the topic of my dissertation, I wanted to combine my research interests with my personal interests. I am a visual learner, and I am good at analyzing pictures. When printed together, the image reinforces the text.

Since the popularity of graphic novels has grown for readers of all ages, and scholars from all over the world have begun to publish critical books and articles about graphic novels, I wanted to explore this research in more depth.

Could you describe some of the works and artists you will be studying?

My area of interest is graphic novels written by francophone writers. Specifically, I plan to study Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, which illustrates the author’s life in Iran and partly in Europe during the 1980s. Another graphic memoir in my corpus is A Game for Swallows by Zeina Abirached, in which the author depicts her childhood growing up during the Lebanese civil war.

As a scholar, how do you approach the literary and artistic medium of graphic novels?

As a scholar, how do you approach the literary and artistic medium of graphic novels?

Graphic novels slip between art and literature. These books have overcome the medium’s criticisms of violence, sexual inequality, and stereotypes of male power, and have earned their place in literary criticism. I try to take into account every single dimension of graphic novels by having a multifaceted approach. I would like to uncover comics’ historical roots and examine how the various genres developed in the West and across the globe, while also delving into the theoretical and formal elements of comics.

Do you currently integrate bandes dessinées in your own teaching?

Yes, specifically in French classes. Our society today is marked by the power of the media, as well as by the considerable presence of images and screens. These changes require a new approach to teaching methodologies for professors and especially language instructors. Graphic novels can be an enriched tool for teaching language, culture, history, and almost anything.

If you could teach an entire course on the graphic novel, which titles would you include? Why?

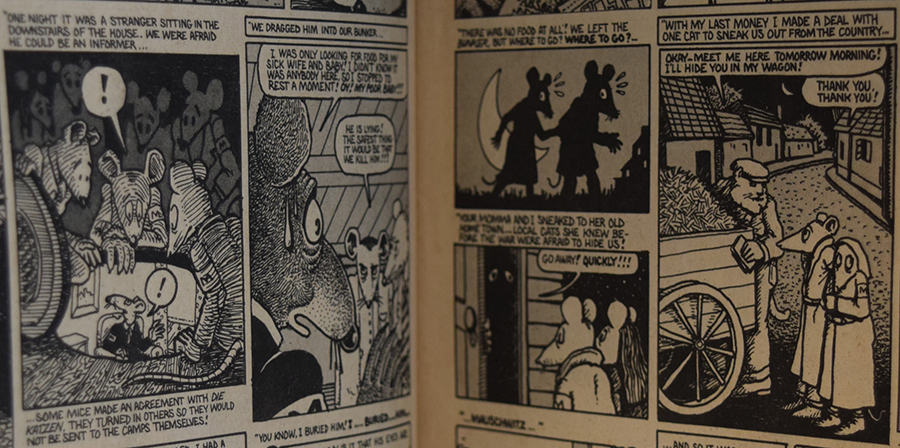

Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Persepolis and of course, The Adventures of Tintin are some of the titles as these books represent turning points in the history of comics.

Images (from the RBS exhibition Comics in Circuit)

Ai’er’re 埃尔热 (Hergé); translated by Huang Zhen 黄珍. Qi ge shui jing qiu (shang ji): Ding ding li xian ji 七个水晶求(上集): 丁丁历险记 [The Seven Crystal Balls (first part): The Adventures of Tintin]. Beijing: Zhongguo wenlian chu ban gong si 中国文联出版公司, 1985. Gift of Michael Durgin.

Robert Crumb, Shary Flenniken, Justin Green, Bill Griffith, Jay Lynch, Michael McMillan, and Art Spiegelman. Funny Aminals, no. 1. Edited by Terry Zwigoff. San Francisco: Apex Novelties, 1972.